The Newton Aycliffe Story

The Beginning

After the Second World War, the North East presented the incoming Labour government with great problems. Coal, steel and shipbuilding were in decline, yet demobbed soldiers needed jobs. Meanwhile, standards of housing in the old pit villages were deplorable. The Beveridge Report of 1942 had pledged to destroy poverty, homelessness, unemployment, ignorance and disease – and the new government was expected to create a ‘Welfare’ state, which would care for its citizens from the cradle to the grave.

ROF Aycliffe, (Royal Ordnance Factory, Aycliffe) was built on an 867-acre (3.51 km2) site off Heighington Lane, Aycliffe, County Durham during the early 1940s. The marshy location was ideal, as the site was shrouded in fog and mist for much of the year providing cover against bombing by the Luftwaffe.

It opened as ROF 59 (Filling factory 8) in the Spring of 1941. It operated 24 hours a day, employing some 17,000 workers in three shift groups and was operational for just over 4 years until the end of World War II in 1945, by which point it had produced some 700 million bullets and countless other munitions. The factory was designated as a ‘Top Secret’ installation and surrounded by high fences with barbed wire.

The workers were mainly women and became known as the “Aycliffe Angels”. During its existence, the factory produced millions of finished munitions including bullets, shells and mines.

Workers were transported from surrounding areas onto the factory site by bus and train, with the mostlocal workers arriving on foot or by bicycle.

The factory was visited during the war years by Winston Churchill and members of the British Royal Family. Many well known entertainers of the day also performed at the factory for the workers.

After the war it was decided to turn it into an industrial estate. Sixty firms set up there, and by August 1946 they employed some 6,000 workers. One of the original firms was Banda – which all old teachers and office workers will remember.

The workers and their families needed somewhere to live, and Aycliffe was proposed as the possible location for a ‘new town’.

Beveridge’s Vision

There was considerable debate about what the new town should be called. Aycliffe Development Corporation proposed the name ‘Newton Aycliffe’, although one councillor suggested that this, as it comprised two words, would confuse the Post Office. Others campaigned for ‘Yackley’, ‘Newcliffe’ and ‘Great Aycliffe’. The people of Aycliffe Village referred to Newtonians – disparagingly – as ‘them up the road’.

Lord Beveridge adopted the new town as the flagship of his new welfare state. He envisaged a ‘classless’ town, where manager and mechanic would live next door to each other in council houses. Newton Aycliffe was to be ‘a paradise for housewives’ with houses grouped around greens, so children could play safely away from the roads.

There would be nurseries (to look after children while their mothers went shopping), a sports stadium, a park, and a ‘district heating system’ so dirty coal fires would not be necessary. The pubs were going to be state-run, and would sell nationalised beer! The town centre was to include a luxury hotel, a college and community centre, a people’s theatre, a dance hall and a cinema. There were even plans to use the Port Clarence railway to give townspeople a link to the seaside. The estimated cost of the town was £10 million; a local politician, Colonel Vickery, called it ‘a scandalous and unnecessary waste of public money’.

Lord Beveridge opened the first house on Tuesday, 9 November 1948. Its tenant was D.G. Perry, an ex-army captain.

A silver spade was used to cut the first sod and was signed by the guest dignitaries. The spade was stolen in 1995, but recovered by police in 2009.

Pioneering Spirits: the ‘fifties

Life was hard for Newtonians in the early days. ‘You have got to have the pioneering spirit’, Beveridge told the people, ‘until you see the town of your hopes and dreams materialise’. And that was just what the early ‘pioneers’ did. In February 1950 the Rev. Tom Drewette – known affectionately as ‘the man in black’ – arrived, and edited a local news-sheet, The Newtonian. His parishioners worshipped in a deserted farmhouse, without electricity or water, using a glass fruit bowl as a font; later when St Clare’s Church was built, it was designed to look like a barn, in memory of those early, pioneering days.

In November 1950 the cow byre at Clarence Farm was adapted into a community centre. The first primary school was held in a block of flats – until 1953, when Sugar Hill Primary School opened. A library was set up in one of the prefabs.

Newton Aycliffe’s gardeners planted crocuses and daffodils (they held the first garden show in September 1951) and Lord Beveridge, who had come to live in the town, organised weekly tree-planting sessions.

By June 1953 – when Beveridge opened the 1000th house (houses were being painted pink and yellow, to prevent the ‘new town blues’) – the Auckland Chronicle was publishing a regular ‘Newton Aycliffe News’ section, reporting the activities of the community association (which met in the granary at Clarence Farm), the cricket, football and tennis clubs, the scouts, cubs and girl guides, a weekly cinema show, a greyhound stadium, a drama group, a Catholic women’s guild, a mothers’ union et al.. There was even a youth club, though it didn’t have many members, for Newton Aycliffe in those early days was ‘a town of toddlers’.

By 1955, the town comprised a triangle of housing, bounded by the Clarence Railway to the south, Shafto Way to the east, and Central Avenue and Pease Way to the north. The population stood at 6,600.

In those early days, every new tenant was vetted by Miss Hamilton (who was quite prepared to tell them to tidy their garden), and personally welcomed to the town by a member of the Community Association; even after 1953, as numbers grew, the Community Association held ‘welcoming parties’ for newcomers.

| New Town Blues: into the ‘sixties | ||

|---|---|---|

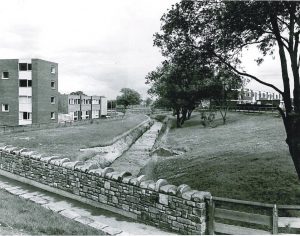

Blue Bridge Blue Bridge |

Methodist Church Methodist Church |

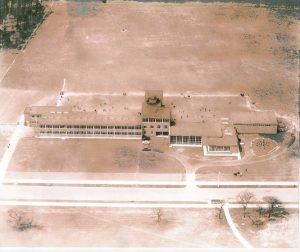

Marlow Hall School Marlow Hall School |

The ‘pioneer’ days lasted into the late ‘fifties. Development continued – St Clare’s Church and Neville Parade

Methodist church were opened in 1955. The ‘Blue Bridge’ was built – so vital a road link that it is represented by the chevron on the town’s coat of arms. The Working Men’s Club was opened in 1956, and Vane Road School in 1959 (when it was described as ‘imposing, bright and spacious’). St Mary’s Church (shown right) was consecrated in 1961, and the Mormon Church – built with the help of visiting American missionaries – was finished a year later.

Behind the scenes, however, problems were arising. A new town needs lots of ‘patient money’ and, by 1957, the government was regretting its involvement. A 1963 White Paper promised ‘to promote … economic activity’ in the region, and an Amendment Order was made by Parliament in 1966, extending the area of the town and setting a new ‘target population’ of 45,000. But successive governments failed to deliver their promises.

Instead, in March 1957, The Daily Express delivered a bombshell. Merrick Winn, in an article entitled ‘The Town That Has No Heart’, lambasted Newton Aycliffe as ‘perfect planning and perfect monotony … nothing to do and nowhere to go.’ Most of all, he criticised the town centre: ‘twelve small shops, a few more half-built, and a keen, cold wind’ (few shopkeepers were prepared to set up in an empty town and wait for customers to move in).

This was the start of decades of criticism in the newspapers of the town’s shops, roads, vandalism and facilities. Articles attacked especially the lack of activities for young people – one youth, reported in 1964, summed up the general tone: ‘It’s a dump, really. There is nothing to do.’

| Visit of Queen Elizabeth II in the ’60s | |

|---|---|

Queen Visits in 1960 Queen Visits in 1960 |

Queen Visits Town Centre Queen Visits Town Centre |

On the other hand, the newspapers (particularly the Northern Despatch, in a column called ‘Newton Aycliffe View’, by Marjorie Spark) reported an endless stream of clubs, trips and shows organised by the people of Newton Aycliffe.

Remembrance Sunday and the Good Friday procession to ‘the green hill’ became annual community events. A festival was held for a fortnight every summer, with a different event each day; later this became the annual Carnival, which survived until 1991.

Rapid Growth: the ‘seventies

The ‘seventies began badly, when T. Dan Smith (the Chairman of ADC) was charged with (and eventually found guilty of) conspiracy and corruption. His successor Dennis Stevenson, however, was young (26), energetic and imaginative, and the 1970s were a time of rapid development for the Town.

In 1974, the Parish Council was re-designated ‘Great Aycliffe Town Council’. The first mayor was local Labour politician Win Dormer. The Council began the annual Bonfire Night fireworks, and an annual civic ball. New toilets were opened in the town centre. In 1974 the Recreation Centre opened – as well as a sports hall and swimming pool, it offered a cinema service, hiring in a programme of films until lack of public interest forced it to stop in 1977. The Burnhill Way Boys’ Club opened in 1976, the same year that the Rotary Club was formed. The next year, a Municipal Golf Course was opened – and at the same time an Angling Pond was constructed. There were even improvements to the town centre. Boots’ opened a large store in 1978, followed by the Fine Fare supermarket in 1979. In 1979, also, a weekly open-air market was started on a pedestrianised Beveridge Way.

ADC also improved its housing stock. After 1976, OAPs were given free insulation and a £300,000 project was announced to convert houses with flat roofs (and put an end to Aycliffe’s ‘little boxes’). By this time, the myth of a ‘classless town’ was considered out-of-date. Private contractors were allowed to build new housing estates – for instance Byerley Park, the Chase and Woodham Village (after 1981). In September 1979 ADC began selling its council houses. By the end of the ‘seventies, new housing had been added in the Horndale, Byerley Park, Chase, Burnhill and Agnew areas. The population neared 28,000.

In 1978, MP Derek Forster called Newton Aycliffe ‘the jewel in the constituency’s crown’ (Aycliffe was in Bishop Auckland constituency) and ADC seemed to be succeeding in its stated aim, to create ‘a self-contained, close-knit community, enjoying good housing and ample amenities.’

The troubled ‘eighties

January 1980, however, opened with news of job losses at Eaton. The news set the tone for the decade. The region lost ‘Development Area’ status, and there was a steady succession of redundancies. The Newtonian called it: ‘death by a thousand cuts’. By 1986, the number employed on the Industrial Estate had fallen to less than 8,000.

There was trouble in the town centre, too. The Thames Centre, completed in 1984, was disappointing. A steady stream of shops closed down. Most blamed high rents; many were family firms that had been there since the early days of the town – Hackett and Baines, Wentons, the Wool Shop.

The newspapers of the eighties give the impression that almost everything was going wrong. In 1982, and again in 1986, there were acrimonious campaigns to close down Greenfield School. The Equestrian Centre held its first event in 1984, and began its long dispute to secure access to the A167 (the failure of which eventually ruined it).

Even the character of the townspeople came under attack. When Burt’s Carpets closed down, the manager claimed that most of his business was DHSS cheques, and labelled Newton Aycliffe ‘Giro city’. A Health Authority survey found that Newton Aycliffe had the highest incidences in the District of solvent and alcohol abuse and marital breakdown.

Aycliffe stopped growing; the population fell, to about 25,000.

ADC had handed over its housing assets to the then Sedgefield District Council (since abolished in the local government reorganisation of 2009) in 1978. It sold the Industrial Estate (to Helical Bar) in 1987, and was dissolved in 1988.

The ‘nineties

After eight years of doom and gloom, things began to change for the better. In August 1988, both Flymo and Tallent announced that they were expanding. Hydro Polymers announced a £50 million extension in 1989, and 3M invested nearly £10 million in its factory. One firm even started drilling for oil! Meanwhile, Sanyo and Fujitsu represented a massive Japanese ‘inward investment’ in the town (by the end of 1994, Fujitsu had invested £300 million in its Aycliffe plant).

In 1997, Newton Aycliffe’s MP became Prime Minister.

Perhaps because the economic climate has been generally more positive, the ‘nineties saw a change in the nature of the issues which concerned Aycliffe people. There were still complaints about lack of facilities – but residents seemed to have accepted that the old ADC vision of ‘a self-contained community’ was impossible. Many people were happy to treat Newton Aycliffe as their home, and the town centre as a convenience, but to look outside the town for leisure and for ‘comparison goods’.

The controversial press issues of the ‘nineties were ‘wheely’ bins, bad neighbours, dog fouling, the state of the ‘Avenue site’ and traffic-calming schemes. The District Council introduced a £1 million ‘Carelink’ scheme, the ‘Community Force’, and, in 1998, a Carers’ Centre. The Town Council’s playgroups registered for Ofsted, became Pre-School Learning centres and an Environmental Ranger was appointed to nurture the Parish’s environment.

In 1998, the town which was Beveridge’s ‘bold experiment’ celebrated its fiftieth anniversary. The anniversary engendered a genuine sense of civic pride. The Town Council made the creation of a circular walk – the Great Aycliffe Way – the central focus of its celebrations. Newton Aycliffe was not and perhaps never could be the ‘dream town’ the early pioneers envisaged, but it had come through the period of its ‘new town blues’.

The new millennium

For a decade, Aycliffe’s MP was PM, and the town became accustomed to being a focus of world attention. In 2000 French President Jacques Chirac dined at the County Hotel in Aycliffe Village, and in 2003 US President George Bush visited Sedgefield Constituency.

Funding poured into local industry, community ventures such as Greenfield Community Arts Centre (2000) and initiatives such as the Aycliffe Church Heritage Centre (2001) and SureStart (2005). In 2008 Newton Aycliffe got a wonderful war memorial, and in November 2009, the Aycliffe Head was lowered into place at the southern entrance to the town; one local wit campaigned for a similar structure to the north, on the grounds that ‘two heads are better than one’.

Despite setbacks, the Industrial Park held its own economically, based on firms such as Filtronic, Tallent, Electrolux and Norsk Hydro. In 2005, the estate was workplace for a workforce of 9000, and in 2006 – as a marker for the future – there was a £1.5 million improvement of the Park’s main entrance (although its big balls attracted some derision).

There was ecological progress, too. The Borough Council began recycling and garden waste schemes in 2003. Aycliffe Village won Northumbria in Bloom in three successive years, 2000-2002.

There was even progress on the town centre. Work on the First Phase culminated in 2003 with the building on the former Avenue site of not only a huge TESCO supermarket, but of a new Youth Centre, an award-winning Town Centre Park, and the first quarter of an impressive central concourse which was to link the new development to the old town centre. In 2006, TESCO conducted a major extension and became a TESCO Extra, revolutionising shopping in the town.

In 2005, the Aycliffe Angels were honoured to celebrate their founding contribution to the town and their service to the country during the Second World War.

But the good times were tailing off. After the collapse of Northern Rock in 2007 and the world financial crisis which followed, the Industrial Park shared in the general economic recession, with job losses and the closure of Schott Glass.

In 2007, also, Tony Blair retired as Prime Minister.

Anger grew as progress ground to a halt on a half-finished town centre marred by an abandoned and rotting Health Centre. There were successive campaigns about the lack of toilets in the town centre. In the 2007 elections, the townspeople vented their exasperation on the local Labour politicians, many of whom lost their seats; for a while, the Town Council was ‘hung’ with 15 opposition councillors and 15 Labour.

These were the years of fears and frustration about terrorism, the Iraq War, global warming, swine flu etc., and the mood of the town dipped with the mood of the nation. There was a sense of disillusionment and fractiousness. In 2004, a campaign group in Aycliffe Village tried (though unsuccessfully) to break free from Great Aycliffe and set up their own Parish Council. In 2008 Woodham Technology College Sixth Form was closed – a major blow to the status of the town.

In 2009 Sedgefield Borough Council was abolished and the town was absorbed into the Durham County Council unitary authority. Soon after, in an acrimonious campaign, the town’s social housing (and a lot of its publicly-owned land) was handed over to a social landlord, Sedgefield Borough Homes.

It seemed as though everything was turning sour.

Into the future…

Against the trend, the 2010s started well for Aycliffe. Phil Wilson, who had succeeded to Tony Blair’s seat in 2007, proved himself an energetic and successful MP. In 2008 he had raised the issue of Aycliffe’s town centre in the House of Commons, and eventually work restarted on the Second Phase in 2011. In the same year, news came through that he had persuaded the government to agree to the development – by the Japanese firm Hitachi – of a new railway factory, a decision which would hopefully secure the town’s economy.

At the start of the second decade of the 21st century – with the 1940s world of the ‘pioneers’ transformed into the high-tech, private enterprise, e-network world of today – our town stares with some trepidation into an uncertain future, amidst national news of economic and environmental crises, government cutbacks and social tensions.

But Aycliffe’s treasures are not, and never have been, in its state-provided facilities; they lie in the character and efforts of its citizens.

And we remain committed to the original vision: to create ‘a town where everyone will want to live’.

Note: There is no adequate history of Newton Aycliffe. Relevant sources include Vera Chapman, Around Newton Aycliffe (a book of photographs); John Wearmouth, This from That (a short history of the Methodist Church) and Stella Aberdeen, Newton Aycliffe 1948-68 (a personal account in the town library). Garry Philipson, Aycliffe and Peterlee New Towns 1946-88, by a former Development Corporation Managing Director, is disappointing. The new town records are ‘official secrets’ and cannot be accessed for 50 years! The County Record Office, County Hall, Durham, however, has five scrapbooks of press cuttings covering the period 1948-1974 (ref. NT/AY2/1-5); and the town library has copies of the Newtonian/ Newton News for the period 1974-present.

In July 2009 Aycliffe Local History Society produced an excellent 90-minute video history of the village, backed up with extensive support materials; in September they held an exhibition celebrating the history of the village. There is also a short video of the Aycliffe Angels story. (Unfortunately both files are too large to show on this website.) There continues a desperate need for somebody to organise an oral history project about the town.Some information in this story was taken from Derelict Places website.”